In agriculture, cultivate makes us think of preparing the soil for planting and tending to crops. When we cultivate we improve something; we foster growth, perhaps by focusing on a particular situation, person or characteristic.

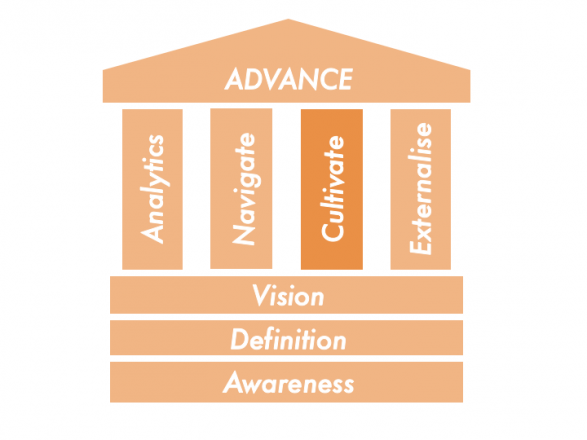

To achieve change that lasts, we are going to have to cultivate those around us (and probably ourselves at the same time). ADVANCE requires us to use data to improve the quality of the decisions we make.

But we can’t rely on the decision-making of one leader, as there is insufficient capacity and capability to undertake the busy operations of a department or institution.

We also know that the academic environment is full of people with a leadership mindset; they want to lead or be led; they don’t warm to directive management.

We therefore need to build a culture that increases leadership capacity, so that more individuals are empowered to take the initiative, but also to ensure that they take initiatives that will move the department forward, not strangle it with uncoordinated conflict.

We don’t necessarily have to create new processes every time we want to initiate change. Some managers do this and create longer term problems for themselves.

Often it’s best to make better use of the existing systems and processes; you might use them in different ways, or increase the value of them. But the key is to save any disruption for specific obstacles.

Culture change, and the processes of cultivating a different group mindset are complex topics. We are not going to address this complexity in its entirety in one article.

However, we are going to explore a fundamental instrument of most organisations – the annual staff appraisal – and examine how a coaching mindset, combined with rational data from the environment, can significantly accelerate your ability to cultivate positive change.

Annual appraisals

The annual staff appraisal can strike dread/apathy/excitement/disappointment into all parties. In many cases, staff may feel that they will have to defend what they have done, or at least make an argument to counter what their manager expects from them.

There is a tension between coaching as a developmental activity, and appraisal, which is something that a coaching manager must navigate carefully.

Managers might want to use appraisal processes and documentation for the purposes of ‘transparency’ – where everyone appears to be set common objectives that can be easily reported on. Inevitably, with such a situation it is difficult to get all staff to play to their strengths. We are all different, and have something unique to offer.

Managers are also being ‘managed’, and therefore they are likely to be required to report when all of their staff appraisals have been completed (are all the forms completed correctly and filed with HR?).

If you have a few appraisals left to do, and they should have been completed earlier, there may be an implicit pressure to ‘get the paperwork done’, rather than fully take advantage of a developmental conversation with a member of staff.

In a university setting there is the additional challenge of working with academic staff. As academics we like to argue and debate; we like to understand what something really means, and feel that we can relate to the context upon which a measure might be applied.

We don’t have a problem with qualitative measures, but the fact that we are comfortable with the fact that we don’t have an answer readily available, doesn’t necessary help the organisation progress.

But academic life can be a relatively selfish pursuit, and if we are thinking, we are learning. As we have explored earlier in this book, academic staff in general respond less enthusiastically to directive management styles, hence our advocacy of the manager as a coach.

But as leaders we should attempt to focus upon activities that deliver value. What is the point of maintaining a dysfunctional approach to staff appraisals, if the mere thought of it saps the life out of us?

However, if you think that you can just dispense with appraisals, then good luck. It would be a bold move to counter the generally accepted wisdom of a large bureaucracy, that has policies for staff appraisals, even though most of the managers see it for what it is.

Of course as leaders we shall tap into our optimism and explore a more positive approach.

Reflection: Reflect upon the conversations that you have had with staff in relation to their performance at appraisal time. Now compare this with your daily conversations. What differences do you observe? How can you transform the annual appraisal conversation with a member of staff?

Perhaps the first issue to tackle is that the appraisal might typically be an annual conversation, and therefore it is too detached from working life. So maybe the first thing to think about is how the annual appraisal can be coupled more directly into the daily conversations.

How can daily dialogue contribute towards the annual appraisal?

What departmental themes could link a staff member’s contribution into the departmental/institutional vision?

If we are going to evaluate performance, what evidence would you expect a member of academic staff to provide?

These questions are much easier to answer if we have a clear vision of what the department/institution will look like, which you will have as a result of the foundation stones of ADVANCE. You will have the confidence that not only is the vision based upon reason and fact, but you will also have involved the same staff who you are appraising during its construction.

If, after all this they don’t know what the vision looks like, how can they translate you aspiration into their daily working lives?

This should give you a clear idea of who falls into the ‘un-coach-able’ club.

As I said earlier, don’t waste energy coaching staff who aren’t receptive to open, challenging, developmental language. Invest in those who have potential, and those who are already performing at a high level.

When you have developed your vision based upon facts that are relevant to your environment, the future is crystal clear. You will have identified the measures/metrics/characteristics that will indicate progress towards your vision. You can feel the future success!

If a staff member can’t ‘feel’ the success, maybe they are a) in the wrong role, or b) in the wrong environment.

You need to exercise some sensitivity in both of these cases. I feel that directive performance management can often ignore these two scenarios (or at least dismiss them, assuming that if someone is truly unhappy they’ll find another job), resulting in frustration for the manager and undue stress and anxiety for the staff (and their families, significant others, etc.).

A coaching manager has to have the mindset whereby they truly want to help people. That includes people who don’t seem to be able to align themselves with the vision. Maybe they have been used to a way of being managed, and your approach is a surprise.

Or they are actually quite fearful of change. Coaching can be quite effective in these situations, particularly if you commit to developing a relationship based on trust.

They need to trust that you are genuinely interested in their workplace well-being. You can only build this trust by being optimistic, honest and generous with them. So, perhaps they are not quite ‘un-coach-able’ yet.

Attendees at my workshops have echoed this sentiment many times; through a coaching oriented relationship they have helped a staff member either align themselves better with a department, or they have worked together to discover what the individual would prefer to do.

When a staff member has a clear vision of what they want, a lot of the barriers disappear. Whilst this may result in the member staff leaving, their departure is because they have found something better for them.

Don’t underestimate the strength of the message that this projects to the immediate environment. When staff leave of their own accord ‘for something better’, they leave on positive terms. The rest of the department will see this; they will already know that a particular individual would not align with the change initiative.

But they also observe an academic manager who reinforced the belief that the staff should be valued, and that means helping them discover their own potential, through a role they are suited to.

The coaching manager does not persecute staff and make them perform against their will.

So, with your measures and vision to hand (which you repeat and make reference to at every opportunity), the daily conversations become easier.

It’s then a process of aligning individual staff capabilities with the departmental themes. It’s about identifying where staff development has to take place – and after a short while, your staff will start telling you what development they need to align with your vision.

As a departmental culture develops, mindful of a clearly articulated vision, the annual appraisal becomes more straightforward. Staff will identify the evidence that is already in place as a result of them aligning themselves to the vision. The developmental conversations will already have started during the year, and will be regarded as continual.

The appraisal will suddenly have found its place – a chance to review progress over an extended period, and an opportunity to think a year or two ahead, as well as to discuss individual staff aspirations. Therefore, the appraisal will have morphed into something that is more developmental.

And this is at the heart of being able to cultivate a culture that wants to continually perform at a higher level.

OK you say, this is all well and good. But at the outset there are staff who will find this approach challenging, and they will make the process arduous. Surely this will bring the whole culture change to a halt?

It is common for the first round of appraisals to be difficult. There will be a minority that welcome the change in approach, fully subscribing to the notion that they can take charge of their own development in the context of improving the department.

There will be a significant portion that are wary, suspicious, and genuinely frightened that they can’t measure up to the vision. Some of them will display apathy (“I’ve seen this before; just sit tight until the next initiative”), some will retreat and become reclusive, and some will generate a veil of enthusiasm, and produce a shopping list of expensive, time-consuming staff development activities.

Beware, because the first request that you turn down could be used as an excuse to suggest that you never really meant what you said in the first place!

And finally there is likely to be a hardcore minority who have every intention of not engaging. They may be frightened, confused, delusional, incompetent or just insecure. Every trick in the book will be used to dodge the process.

Some managers see this as a game, with the objective of trying to ‘outwit’ their ‘opponents’. Unfortunately there are many examples of this approach being legitimised, in that the measured performance improves.

Of course in such situations it is unlikely that a longer term vision has been created and it is the short-term transformation of numbers that is reported as a success. Nonetheless, the cost to the environmental culture can be quite damaging.

As an academic coach you’ll persevere beyond the initial challenge as you’ll have confidence in the long term view. The measures you will have chosen will be based on the data that you have reasoned is important.

In time, some of the hardcore will come round and realise that it might be interesting to engage after all, especially since the manager seems to want to help staff.

The second round of appraisals is where managers see the greatest transformation. The keen early adopters are already bearing fruits of their focused engagement, and doing things that are visible to the rest of the department.

They’ll already be in a position to Externalise. Success in acquiring one or two small funded projects can do wonders for the self-confidence, motivation and external visibility of an academic, which of course you will be supportive of.

While hard-liners will still be resisting, the rest of the department will have started shifting. They’ll have witnessed the successes of the early adopters, and some will have got themselves involved already.

Others will test the water by suggesting some new activities that they would like some development for. Some will be bold enough to set themselves a target to achieve for the coming year.

By the third appraisal the bulk of the changes will have been made. Staff will have discovered what they like doing, to what extent it can be accommodated (usually the department is more flexible than people think), and have witnessed the benefits to them personally, all wrapped up in a department that is performing better.

If during this period your department has recruited new staff, then the transformation is accelerated significantly. The new starters come in fresh and adopt the developmental approach without being held back by any prior cultural baggage.

What is important to remember that if you actively monitor and measure performance in a directive way, the annual appraisal will remain the key event on the calendar to report achievement.

In contrast to this, a coaching-oriented style positively supports development on a continual basis, meaning that the annual ‘check-in’ can be more focused upon the strengthening of core values and the development of longer term career goals for an individual.

So, you have it within your power to re-purpose the staff appraisal process and it’s an excellent instrument to cultivate higher performance.

Reflection: What are the potential benefits of planning to develop role models in your environment? What can staff learn from a role model?

Exercise

A key tool of culture change is how you approach the appraisal and development of others. To do this you must familiarise yourself with the current staff appraisal process. Sometimes this is referred to as a ‘cycle’, or a ‘developmental review’ and there may be key points in the annual calendar at which point certain activities are undertaken.

Once you have oversight of the process, look for ways in which your vision and measures can be incorporated into the cycle. For instance, do you have an event whereby a line manager discusses the objectives of the department for the coming academic year?

As a coaching manager you are more likely to use this departmental objectives as prompts for developmental requirements for the individual concerned.

If all staff need to produce two published outputs this year, what support will each of them need? Some will need more support than others.

Depending upon your procedures for appraisal, you need to either rework the forms/processes etc., for your own purposes, or you should provide an addendum that enables the explicit links to be drawn between the departmental/institutional objectives, and the individual’s developmental requirements.

The purpose of the addendum is to explicitly highlight the linkage between an individual’s contribution to the larger environment. This helps everybody by making clear what needs to happen, and prompts them to think about the support they need to help the department achieve its target.

Developmental conversations that start with this tend to productive. Sometimes an individual will not feel able to respond; this is OK as well, as the process of helping them complete it is another fantastic coaching opportunity.

If we look at some extracts from a developmental objective setting form (Tables 2 and 3), we can observe the link between departmental target, an indicator of what successful achievement looks like, a space for he individual’s contribution as to how they shall engage, and a date by when it needs to be concluded.

This both prepares the groundwork and frames a coaching conversation in terms of the individual’s development. The key question for the individual is:

“What development support do I need to achieve my objectives?”

You might choose to add this to your form, to be completed as an outcome from your meeting.

|

Departmental target |

How will we know when this has been achieved? |

How will you provide evidence of your engagement? |

By when? |

|

Improve student satisfaction score across modules taught |

85% of the students will report ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ |

End of Semester |

|

|

Improve first-time pass rate |

80% of the students will pass first time and progress |

End of Semester |

|

|

Improve student achievement |

60% of students achieve at least 2:1 or First |

End of Semester |

|

|

Provide timely, constructive, written feedback to students |

100% of summative assessment feedback received within 4 weeks of submission deadline |

End of Semester |

Table 2. Extract from the teaching quality section of a development review form.

|

Departmental target |

How will we know when this has been achieved? |

How will you provide evidence of your engagement? |

By when? |

|

Improve quality and volume of research output for the department |

Principal researcher: 6 peer-reviewed articles, >2* Researchers: 3 peer-reviewed articles, >2* Other staff: 1 peer-reviewed article, >2* |

End of year |

|

|

Improve the external esteem of the department |

Principal Researchers: 2 research events organised/edited books/edited journal special issues Researchers: 1 research event organised/edited books/edited journal special issues |

End of year |

|

|

Improve the research environment |

Principal Researchers: attract and supervise 1 new PhD student Researchers: attract and supervise 1 new PhD student |

End of year |

|

|

Increase research funding into the department |

Principal Researchers: achieve at least one successful bid >£150k as Principal Investigator Researchers: submit at least 2 applications for funding >£10k Other staff: engage with at least 1 funding bid submission |

End of year |

Table 3. Extract from the research section of a development review form.

Using the above as a guide, take the measures you identified in Definition and Vision, and create a document that can be used to augment your existing developmental review/appraisal documentation.

Leave a Reply