Abstract

This article explores the challenges of managing research and teaching in UK Higher Education, by examining the variability of boundaries that are drawn around such spaces. Changing policy in the UK is provoking Higher Education Institutions to respond in dierent ways, to address the emergence of quasi, and ultimately, free market conditions. In particular, we examine how differing management and leadership cultures, namely mangerialist and collegial, can impose more or less constraints upon research and teaching management, as both discrete and combined activities. Furthermore the potential interplay between research and teaching is examined with a view to exploring a new model of university management, that has departmental leadership as a core component of a more de-coupled strategy. Finally we consider the implications of such thinking upon institutional management and leadership, and conclude that the emerging complexity in the UK HE sector is demanding a more adept leadership culture that embraces emergence and the development of a holistic understanding of research and teaching.

1 Introduction

This article considers the management of research and teaching in terms of the constraints that are often imposed upon each set of activities. This is a complex, challenging issue for university managers, and ultimately, institutional leaders. Firstly, a brief synopsis of relevant events in the development of Higher Education in the UK is discussed, to set the context for the rest of the discussion. Pertinent concepts are then described, before the limits upon the management of research and teaching are explored. Finally some implications for University management are described. We begin by considering how the United Kingdom (UK) Higher Education (HE) sector has been developing of late.

2 The higher education context

Universities have been considered to be collegial institutions, consisting of scholarly academics who create and disseminate new knowledge. That knowledge is imparted upon a community of students, who after a period of time, acquire a degree and move on within the wider economic community. The scholarly pursuit, perhaps as a means in itself, would be a key motivation in such an environment. Government policies that apportion funding to universities, would insulate a Higher Education Institution (HEI) from accounting for its activities, unlike private industry that needs to create financial profit now and in the future.

Those who are employed in a UK HEI understand that this halcyon description lies some distance from the reality. For some time now, UK Government policies have steadily influenced HEIs by augmenting different sets of conditions upon how a university might function. An emerging need to demonstrate that the public funds are been spent wisely and appropriately, has led to substantial effort being expended upon the quality of an HEI’s provision. The UK Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) has substantial influence over the way in which a university manages its processes, and when this is combined with strictly enforced guidelines from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), a university can find itself needing to react to these constraints.

The objectives of HEI management thus become more defined than the traditional, nebulous pursuit of knowledge. Queries from funding bodies require managerial systems to provide the requisite information. Activities that were once undefined, become scrutinised in terms of resource consumption, and whether the activity itself provides `value’. Indicators of performance become more overt, with league tables appearing that rate institutions on their relative results for teaching, research, employability and `student experience’. The recent trend in the introduction of partial fees, and latterly, whole fees (albeit capped at certain thresholds at the time of writing) has introduced a quasi-market environment in which UK HEIs function (Le Grand and Bartlett, 1993).

The requirement to report upon performance sharply opposes the more collegial culture of HEIs. As institutions begin to focus upon the minutiae and install systems to manage performance, efficiencies in the way individual staff work are immediately called into question. Activities that were once regarded as part of the norm, are now exceptionally identified as being wasteful or redundant when considered at the micro level. Staff find that as a direct consequence of the systems being measured, that their own performance is assessed and reported, leading to an implicit pressure to do more with less (Smyth, 1995; Cuthbert, 1996). In times when external funding is reduced, that implicit pressure becomes explicit as academic managers direct and control the activities and working conditions of academic staff (Trowler, 1998).

From a cultural perspective, there appear to be HEIs who are more ready to accept managerial practices than others. Pratt (1997) identifies the general polarisation of institutions that existed before 1992, and those that were formed post 1992. Universities that existed prior to 1992 had traits of a more collegial culture; a model of governance, rather than command and control management, was more evident in their daily operations. Conversely, as polytechnic institutions became able to use the title of university post 1992, the traditional bureaucracy associated with Local Authority management tended towards a more actively managed culture, though not to the extent of a private company. McNay (1995) observed that the generalised differences between this bipartite split in the sector, have started to diminish in the light of changing funding policy.

Specifically, both parts of the sector are operating under the same funding regimes, and are observed and reported upon by identical agencies such as QAA.

3 Managing operations

As the HE quasi-market has developed, universities have undergone transformations in an attempt to adjust to the more explicit demands that are placed upon them. The increased desire to act rationally, is one example of how internal decision making has been affected by economic pressures.

University managers have used private sector management approaches as inspiration for their re-interpretation in the HE sector, which is often referred to as new managerialism (Reed and Anthony, 1993; Clarke and Newman, 1994; Deem, 1998). We now consider the two most significant spaces within HE, research and teaching, and explore the limits by which pertinent activities within those spaces can be managed. First of all, we shall consider the research space.

3.1 Managing research spaces

To understand the constraints of research requires some understanding of what research is, if only to clarify its distinction from teaching. For the purposes of this discussion we assume some basic definitions from Bushaway (2003) as follows:

- Research. Using a systematic process of enquiry to undertake some original investigation, leading towards new knowledge or new under standing.

- Research leadership. Understanding the research context, setting goals and enabling research to be directed.

- Research management. The control and coordination of research activities to ensure its correct operation.

- Research coordination. Managing resources in relation to research objectives, maintaining appropriate accountability within a university.

- Research planning. The creation of a research strategy that is congruent with the aims of the university.

- Research support. Creating and maintaining an environment in which research activities can flourish.

Furthermore we assume that research is funded by an external source, and therefore other forms of research activity that a university will typically undertake, such as scholarship (Dearing, 1997), the application of knowledge, and the development of learning and teaching materials, will not be considered within the scope of this discussion.

The management of research requires an appreciation of project and finanical management, quality assurance, logistics, human resources, administration, marketing and networking (Bushaway, 2003). Since it is externally funded, key stakeholders demand progress to be reported and results to be evaluated. All of these tasks must also be auditable. Thus, the assessment of performance is an important activity for the management of research, and whilst research might be considered a creative discipline, there is much that must be managed if the discipline is to be a sustainable income stream for a university.

It is the creative part of research however, that is influenced by the need to manage and account for research performance. As funding councils and bodies demand more tangible evidence of `impact’, whether it be social or economic, research is ultimately affected by the thrust of evaluation. `Blue sky’, high risk, high reward, research is becoming increasingly difficult to conduct, as funders become more prescriptive with their desire for evidence.

As such, whilst funded research generally lends itself to managerial activities as the measures are generally well-defined and apportioned to a finite budget, the very nature of the requirement to demonstrate tangible outcomes, limits opportunities to take risks and conduct truly innovative investigation.

To summarise, externally funded research is actively managed and sits comfortably in an environment that measures, monitors, reports and manages performance. Management of the creative aspect is somewhat different and thus presents a boundary beyond which management activity is less productive and may even harm outputs.

3.2 Managing teaching spaces

At first sight, the management of teaching spaces would seem to be determined by finite sets of resources such as, facilities, staff, programme timetables, specialist equipment, length of module or programme, etc. Within this there is the knowledge capability of each staff member (what they can teach), and the interplay between different subjects upon a learner’s (and an academic’s) timetable. For example, an academic may teach two closely related modules and another might teach three disconnected subjects, with a clear difference in the workloading between both situations. Other, discrete constraints are how much time staff can make available; teaching duties assumes the inclusion of other activities that are distinct from teaching itself, such as administration, pastoral care, attendance at departmental meetings, marketing and open days.

The management of these constraints can often focus around a normative currency, which is often time-related in terms of the number of hours `contact’. Contact refers to the amount of hours a tutor spends with students face to face; immediately this does not take account of electronic interactions and communication, which as technology becomes ever more pervasive, is an increased part of the academic’s working life. Using the currency of contact, systems emerge whereby other activities are converted into `contact hours’, so that they can be included as part of an overall assessment of an individuals workload. The manifestation of all the teaching constraints may result in a delivery norm of 1 hour lecture and 2 hour tutorial per week, per module, for example.

The interpretation of this varies in relation to management style, as well as the characteristics of the academics being measured. Such styles range from trust-based laissez faire approaches, through to more prescriptive models that attempt to account for all activities. The reporting of teaching outcomes is challenging, since it is considered to be largely based upon qualitative data, yet there is often a demand to report it quantitatively in order to `benchmark’. The evaluation of teaching itself is a complex topic, especially when we consider the ethical constraints that are imposed upon studies of teaching practice. Dearlove (1997) argues that resource constrained teaching activities can be managed effectively, but the remainder can only be facilitated.

Thus, the management of teaching (and teaching related activities) is often interpreted as the management of performance and culture, in response to the conflicting demands of the external HE environment as discussed earlier. In contrast to teaching delivery, scholarly activities are perhaps more nebulous to account for, and there is a tendency either to assume that an academic makes a professional judgement as to the hours they invest, or a nominal block of contact hours (referred to as self-managed time, which is outside of teaching periods), is used for the purposes of representing workload. There may of course be discrete activities such as writing an academic article, authoring a book, writing a funding bid or conducting a scientific experiment, that some attempt can be made to forecast the time required.

In particular, a pedagogic experiment may be part of some externally funded work, where constraints were imposed at the design and planning stages of the bid application. Such work may be assumed to be more defined.

As such, the complexity of the teaching role means that significant portions of the workload are both variable in scope and size, and challenging to account for. How does an academic manager assess the teaching quality of an academic? Assessment characteristics might be the number of complaints received, or the average grade profile of the student cohort, or even the overall student satisfaction as reported from an end of module questionnaire.

However, all of these measures are open to manipulation, but also they can also be considerably influenced by external factors meaning that they cease to be a reliable measure. For instance, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for grade performance (the percentage of students who achieve 2:1 honours or above), does not take account of the ability of a particular cohort. In a climate where students are demanding more specialist programmes, smaller cohorts will demonstrate more volatile performance statistics. This complexity, and the arguments within, create an extremely challenging environment for the academic manager of teaching spaces. Academic staff understand too well the relative difficulties of attaching measures to teaching quality, satisfaction, retention, progression and achievement. Such understanding leads to frustration and tension when the measures report adverse conditions that may be beyond the influence of the staff, and of course, staff may respond to the role of measurement by performing strategically.

However, there is clearly a conflict between the ability to measure, monitor and control sizable aspects of the teaching role, in an environment that is demanding its effective management.

4 Managing research and teaching spaces together

Whilst each space has its own constraints, there are also limits imposed when the two activities are combined. Indeed, universities have a need to consider the two spaces not only as separate entities, but also as the fundamental constituent activities of a HEI. It follows that the complexities of managing the spaces separately is further complicated when they are brought together.

The character or self-perception of an institution may impose constraints upon these activities. The simplest example is whether an institution regards itself as research or teaching intensive. Since universities are typically large organisations, that are composed of smaller units, the relative achievements of a particular unit may appear to be at odds with the overall perception of the institution.

For instance, a small department that has aspirations to improve its research outputs and reputation may decide to submit grant applications, and therefore will be actively promoting the inclusion of research as part of its strategic plan. In a teaching-intensive university there maybe countless hurdles to overcome, since the operations will tend to reflect the predominant activities, which may not be conducive for funded research.

Dedicated research administration and support may not exist for instance, or have insuficient capacity for certain types of projects. The academic staff time will not formally be available, since the HEFCE funding received is restricted to teaching duties and is not for the pursuit of research monies. As a consequence staff may invest their own time to write bids, until they achieve their first successful grant. This grant will then be used to `buy them out’ of teaching, or in other words, spend less time with students. This behaviour reinforces the divide between research and teaching, especially when teaching colleagues see research active colleagues’ careers progress at a greater pace.

Loosely-coupled departmental structures, together with collegial tendencies, might be ideal conditions for teaching excellence. They are however, environmental conditions that are less than ideal for the monitoring of measurements, such as costs. Additionally, they are tolerant of poor teaching quality since it is dicult to directly challenge and manage performance that is below that what is expected. Clearly, in an age where the control of costs is mandated by external factors from free market or quasi-market forces, there is a boundary to be placed upon laissez faire cultures (at the potential expense of teaching and research quality). Conversely, managerialist practices can stifle creativity and engender educational approaches that are based on training models, rather than fostering learning through exploration and the creation of new knowledge.

Many academic staff feel that a hard boundary exists between research and teaching spaces, even though staff may be expected to contribute to both spaces in pursuit of the university’s mission. One such reinforcement of the boundary between research and teaching is that caused by the differential in funding for either activity.

Resources for teaching have been steadily reduced and replaced with systems for Quality Assurance (QA). These systems are discrete from teaching activity and have served to considerably increase the administration workloads of academic staff (J.M. Consulting Ltd, 2000), whilst demonstrating no obvious support for research (Brown, 2002). QA systems are essentially managerial, causing tension when the activity to be observed does not lend itself towards direct comparison with `benchmarks’.

There is an irony that after successive years of research funding being awarded through the UK Research Assessment Exercise (RAE, now the Research Excellence Framework, REF), teaching-intensive universities, who generally have not achieved the research esteem of research-intensive universities, are now motivated to acquire esteem and compete for funding with the HE sector at large. The motivation for this change in behaviour has been in part, the publishing of university league tables such as the Guardian newspaper (http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/table/2011/may/17/university-league-table-2012), which attempt to indicate the relative performance of each institution against each other. Having a value greater than zero in the research column is one strategic way of propelling an institution further up the league.

However, this change in strategy means that tensions that may have existed amongst academics who fight to continue with their own research against a backdrop of a full teaching workload, must now become more exposed within departments, faculties and ultimately the institution itself.

Clearly, institutions that decide to undergo a transformation have made a conscious choice to re-engineer their culture, and how that culture is managed. This has implications for the university management, who must recognise the limits of research and teaching management, both separately and together, with a view to pursuing a successful strategy.

5 Implications for university management

Within the quasi-market (Le Grand and Bartlett, 1993) of UK HE, external factors such as reduced funding, quality assurance compliance and reported performance through league tables and student satisfaction (National Student Survey), mean that HEIs have a need to manage and improve performance. As discussed earlier, the management of research and the management of teaching exposes different limits.

Research has a history of having to be accountable for external stakeholders, and therefore its management has developed upon a more rational basis. Teaching however, has been funded differently, in a way that has insulated expenditure from free-market volatility in the main. When cuts in teaching funding are announced, they are typically met with some objection. Within this funding model, certain acivities relating to the consumption of resources are straightforward to manage.

Some aspects, generally related to the quality of teaching and the `learning experience’, are more difficult. Performance management in university culture is a very challenging topic, and one which has significant implications for HEI management.

The first implication is that the university must have a clear understanding of its purpose. The categorisation of `research-intensive’ and `teaching-intensive’ will become less relevant as institutions attempt to performance manage both research and teaching to respond to external measurements.

Indeed, institutions who still have collegiate approaches to managing teaching, alongside managerialist approaches towards research, may have a more challenging time in the emerging marketplace. Post-1992 institutions, with histories of bureaucratic teaching and QA management, may adopt more readily, the disciplines of managed research activity.

However, the managerialist approach is essentially `top-down’ and this presents a risk that the collegial, creative environment where ideas emerge and flourish, will be silenced by KPIs and committees.

Shattock (2003) argues that the environmental conditions for change are more likely to exist in a university that fosters a more holistic, emergent approach to strategic management. Since both research and teaching are two fundamental constituents of a HEI, then university management must consider the institution’s strategy in a holistic manner. This contrasts with institutions that have separate research and teaching strategies (with no obvious links between the two (Gibbs, 2002)), managed by separate Pro Vice Chancellors.

Henkel(2000) advises that the identities of instutitions have developed over a long period and therefore they may offer some considerable resistance if the future appears to be fundamentally different. Even if the perspective exists that research and teaching may be separate islands in an institution, the creation of explicit, positive links between the two is not easy to manage (J.M. Consulting Ltd (2000), referred to in Locke (2004)). Dearlove (1998) suggests that a close understanding of how the culture functions, especially its strengths, will be instrumental for university leadership to consider through a period of transformation.

From an institutional perspective there should be strategies for research and teaching. However the implementation of these strategies is less complex if there are explicit links between the strategies; separate PVCs, with disconnected strategy documents, only create difficulties for departmental management. Therefore there should be explicit, appropriate links between the two strategy documents (if one, unified strategy is a bridge too far), indicating their mutual contribution towards the mission of the institution. For instance, `teaching informed by research activity’ is as important a statement as `the processes of research informing the teaching’. The nature of scholarship is a too broad and contested term to be the only documented nexus (Neumann, 1994) between teaching and research, and assumes that it is interpreted consistently across all functions.

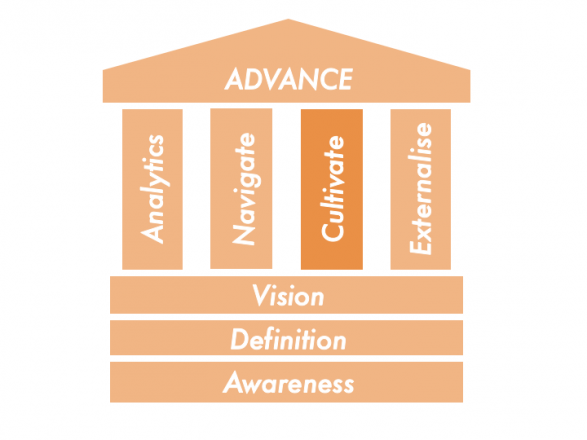

Therefore, the facilitation of an emergent environment where the holistic strategy is described by the university’s executive, to be interpreted and operationalised by departmental units, should be a key aim for an HEI. A university that has a culture of flexibility, being able to adapt to emerging trends, will be better placed to accommodate medium-term transformational objectives such as engaging with funded research for the first time.

Understanding the core purpose can then set the scene for departments to scrutinise their own means of achieving the institution’s goals. To prevent departments from crudely interpreting the university mission, there is an implication for the institution’s Human Resources function, which must address a historical disparity between the careers of research active academics and teaching academics (Locke, 2004). A related matter is that of recruitment; institutions may choose to be more selective with the appointment of new staff, to align better with the emerging values (Locke, 2004).

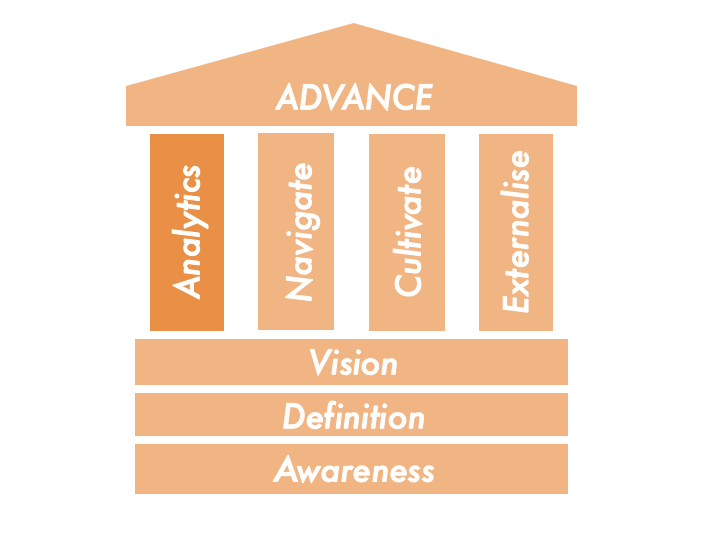

The adoption of an emergent approach means that leadership should not be confined to the senior management tiers. For departments to be able to interpret the institution’s goals, and thus develop their own strategic response, leadership roles must be cultivated at departmental level also. These leaders will manage, support and facilitate (Middlehurst and Kennie (2003) referred to in Locke (2004)) the real agents of change – the academics – in order to develop responses to tensions between the core components of university operations, research and teaching. This may inform the conversations around scholarship; what it is, and what it means in the context of the academic role.

Whilst there may be a conceptual linkage, for scholarship to act as the nexus betwixt research and teaching (Elton, 2005), it is for the actual practitioners to work this out in their own context.

6 Conclusions

The question as to whether there are limits to the management of research and teaching is a pertinent one for UK HEIs at this time. New managerialism can be seen as a way of `grasping the nettle’, and undoubtedly some aspects of a university’s mission, that being funded research and the resource management for teaching, appear to be suitable candidates. In fact, institutions are already demonstrating evidence that they have adopted this approach.

However, the realisation that managerialist, top-down approaches may also have negative connotations for the other functions of a university – high quality, inspirational teaching, scholarship and research creativity – has severe ramifications for the approach that university management should take.

It would seem that a leadership model of trust should be adopted, whereby an open and honest discourse is held to understand the current identity of an institution, as well as a future identity that the university might want to aspire to. This would then be transposed into a set of goals to be interpreted at departmental level, to reflect the cultural and subject discipline norms, the capabilities of the staff, and indicate some of the uncertainties for the future. The university Human Resources department must also prepare to facilitate the development of departmental leadership, fostering an environment where leaderly talent is nurtured, whilst also developing and enforcing policies that make staff recruitment more agile and a better fit for the needs of the departments.

In conclusion, as HEIs operate in an `age of supercomplexity’ (Barnett, 2000), a suitably adaptable approach to management is required. Paying homage to collegiality will demand leadership at all levels of the institution, to effectively manage a shared understanding of what the core function of a particular university is. This understanding will be derived by considering the limits of research and teaching management as a holistic entity, without resorting to a corporate management approach to performance measurement.

References

Barnett, R. (2000). Realising the university in an age of supercomplexity. Society for Research into Higher Education. Open University Press, Buckingham.

Brown, R. (2002). Research and teaching: repairing the damage. Exchange, 3:29{30}.

Bushaway, R. (2003). Managing Research. Managing Universities and Colleges: Guides to good practice. Open University Press and McGraw-Hill Education, first edition.

Clarke, J. and Newman, J. (1994). The managerialisation of public services. In A. Cochrane and E. McLaughlin, editors, Managing Social Policy, pages 13{31}. Sage, London.

Cuthbert, R., editor (1996). Working in Higher Education. Open University Press, Buckingham.

Dearing, R. (1997). Higher education in the learning society. Technical report, The Stationery Oce, London.

Dearlove, J. (1997). The academic labour process: From collegiality and professionalism to managerialism and proletarianisation? Higher Education Review, 30(1):56{75}.

Dearlove, J. (1998). The deadly dull issue of university administration? good governance, managerialism and organising academic work. Higher Education Policy, 11(1):59{79}.

Deem, R. (1998). New managerialism and higher education: the management of performances and cultures in universities in the united kingdom. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 8:47{70}.

Elton, L. (2005). Scholarship and the research and teaching nexus. In R. Barnett, editor, Reshaping the University: New Relationships between Research, Scholarship and Teaching, Society for Research into Higher Education, chapter 8. Open University Press, Maidenhead, first edition.

Gibbs, G. (2002). Institutional strategies for linking research and teaching. Exchange, 3:8{11}.

Henkel, M. (2000). Academic Identities and Policy Change in Higher Education. Jessica Kingsley, London.

J.M. Consulting Ltd (2000). Interactions between research, teaching and other academic activities. Technical report, Higher Education Funding Council for England, Bristol.

Le Grand, J. and Bartlett, W., editors (1993). Quasi-markets and Social Policy. Macmillan, London.

Locke, W. (2004). Integrating research and teaching strategies: Implications for institutional management and leadership in the United Kingdom. Higher Education Management and Policy, 16(3):101{120}.

McNay, I. (1995). From the collegial academy to corporate enterprise: the changing cultures of universities. In T. Schuller, editor, The Changing University, pages 105{115}. Open University Press, Buckingham.

Middlehurst, R. and Kennie, T. (2003). Managing for performance today and tomorrow. In A. Hall, editor, Managing People, Society for Research into Higher Education. Open University Press, Buckingham.

Neumann, R. (1994). The teaching-research nexus: applying a framework to university students learning experiences. European Journal of Education, 29(3):323{339}.

Pratt, J. (1997). The Polytechnic Experiment, 1965-1992. Open University Press, Buckingham.

Reed, M. and Anthony, P. (1993). Between an ideological rock and an organizational hard place. In T. Clarke and C. Pitelis, editors, The Political Economy of Privatization. Routledge, London.

Shattock, M. (2003). Managing Successful Universities. Open University Press, Maidenhead.

Smyth, J., editor (1995). Academic Work. Open University Press, Buckingham.

Trowler, P. (1998). Academics, Work and Change. Open University Press, Buckingham.